The last few years has seen a resurgence in films telling the story of journalists, from Spotlight to The Post to Frost/Nixon to She Said. Each of them have all decided to show different aspects of the craft, depicted different stories, and they have each had different areas that stood out. And whilst not all of them were commercial hits, She Said being an unfortunately poignant example of this, each of them at least settled on their own identity, not trying to be any more metaphorical than was needed – primarily because the story they were each telling was one well versed in the Zeitgeist of the audience coming to it. Civil War doesn’t have that luxury. Or hinderance, depending on who you ask. But what it does have is a crisis of identity right at its heart that, days after first watching it, it has left me wondering what the film wanted to be.

Alex Garland is not one new to metaphor. He’s not one new to straddling a complex line of storytelling and trusting his audience to find their own interpretation. At the same time though, he’s not one to shy away from a specific message (one would be hard pressed to say Men tried to hide its central argument). But Civil War is constantly trying to decide what it wants to say and how it wants to say it. Its plot and characters and story telling devices are constantly swinging either side of a knife edge between giving too much detail away and holding too much back. It’s central premise that California and Texas have split off, seceded and united in a faction to bring down a fascist ruler, unwilling to give up their seat in power, is one that never gets addressed other than acknowledging the actual union. No thought or time is given to what must have happened for these diametrically opposed states to decide that their best interests were served working together. No time is spent with characters from either side understanding the workings of this alliance that would justify the necessity of their co-operation – an understanding that could have been as interesting as the rest of the film. Instead, we spend our time with four journalists travelling from New York to DC on a quest to interview the President before he is removed from power. It’s a tactic that allows Garland to show you a lot of the world in a very compact space, but one that brings with it limitations that almost hold the film back from pushing itself further.

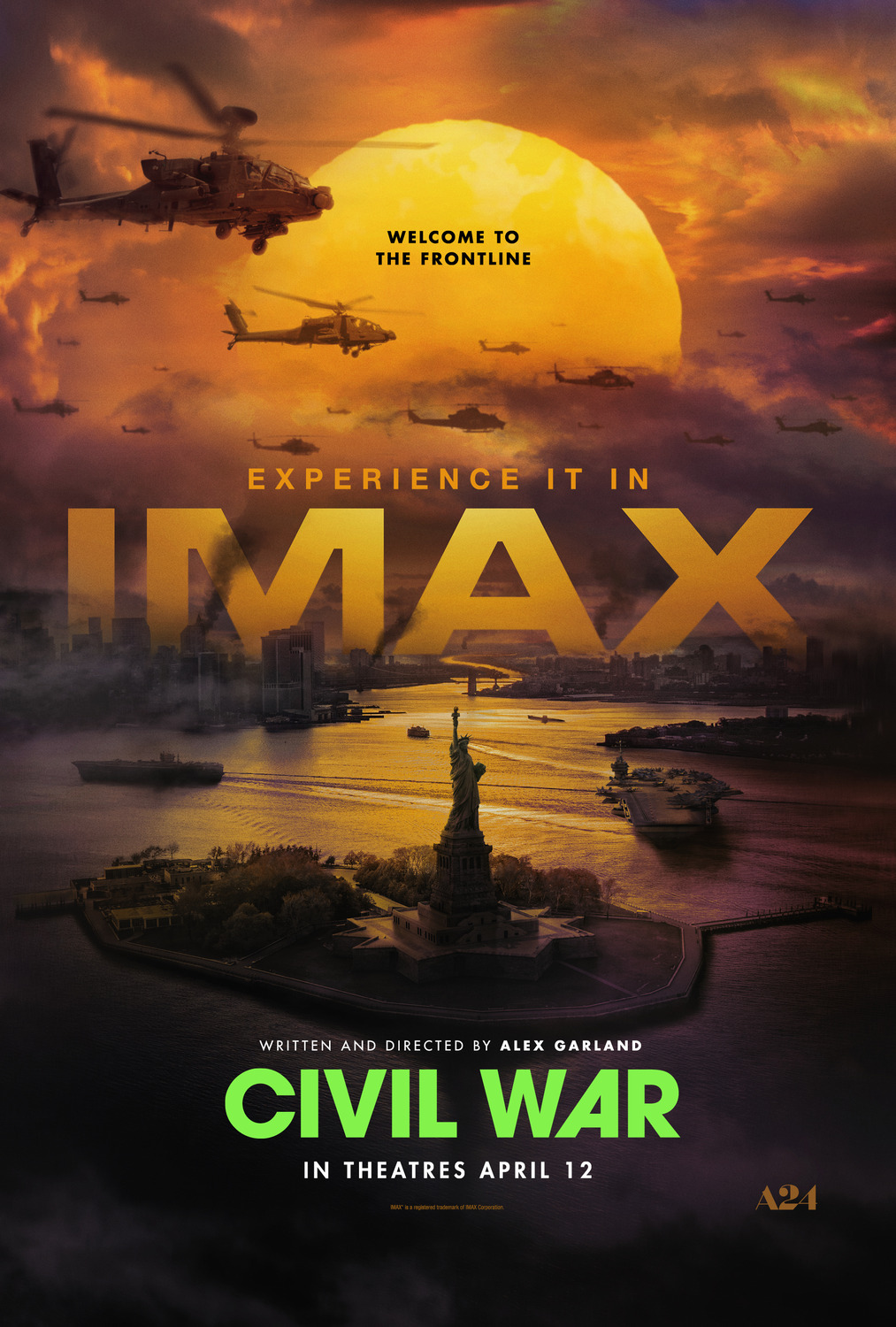

I’ve seen this film twice now, once at the BFI IMAX on its opening night, and once in Screen 2 at the Odeon Leicester Square and they were two very different experiences. Not just from the obvious fact of the difference in the size of the frame we’re seeing but the impact this has on the film – this is a story much more well suited to the smaller screen. For the vast majority of its run time we’re sticking with the same four people, crammed into a car travelling the North Eastern US countryside, or following soldiers clearing out buildings in firefights, or tucked into tight spaces whilst snipers wait each other out. It’s a film whose frame almost feels like its squashing the image from each side and the story is trying to fight its way out, mirroring the central conflict at its heart. On a smaller screen, one gets a much better sense of this. One feels far more stuck in the thralls of the action with the journalists, the bullet cracks echo louder, and the explosions shake the frame with renewed vigour. But given all this, it’s a film still boasting about an IMAX release, still marketing itself on the final half an hour, with trailers that almost want you to ask if this is the latest Marvel property. It’s a film whose very viewing options are as deliberately confounding as the politics at it’s heart.

But the problem is, none of this is accidental. Garland has deliberately placed these idiosyncrasies all throughout the story. He consciously chooses not to tell us whether the “Antifa Massacre” mentioned was one where the group committed a massacre or were themselves devastated. There are never any mentions to specific political parties or real politicians. And not once are we ever shown any of the build up of the events that led to the outbreak of the war. We only ever hear mentions to these instances and must interpret the details from the way the characters talk to each other. Garland has taken a definitive step to make this a film that people from both sides of the isle could come to and not immediately feel like its taking a stance in either direction. As was the case when Dune: Part 2 arrived, there will undoubtedly be hardline right-wing nuts who decide Civil War is taking shots at the current US President and is agreeing with all their Q-Anon based conspiracy theories. They won’t take the time to process for a moment, the very clear and unabashed analogies being made against Trump (and other fascist icons). Garland has made sure that the characters in this film don’t take a stance either way, leaning very dearly into their obligations as a journalist that they just present the facts and let other people make the assumptions. But Garland himself, with very little obfuscating in interviews, is all too clearly presenting this as his thesis against fascism. As a warning that this is not a future all too far out of reach with the rhetoric going around the annals of not just America at large, but in the corridors of power around the world.

My thoughts on this film have swayed many times since first seeing it. At times my brain wants to say that it sits up there with the best of Garland’s work, Ex Machina and Annihilation. But then comparing it to those, where he doesn’t ever feel like he’s holding back, almost tarnishes the memory of the other two. In the end I feel like it will be a project of his debated for a while until it finds a home outside of theatrical presentation, when people viewing it either for the first time, or revisiting it, realise that it is a project more at home in a smaller setting. Where the claustrophobia of the country one travels round suddenly feels much more intense.

Leave a comment